Why does 304 stainless steel rust after machining?

Blog post description.

heweifeng

12/3/20254 min read

Why does 304 stainless steel rust after machining?

How can we unravel the confusing symptoms and systematically identify the root cause and pattern of this defect?

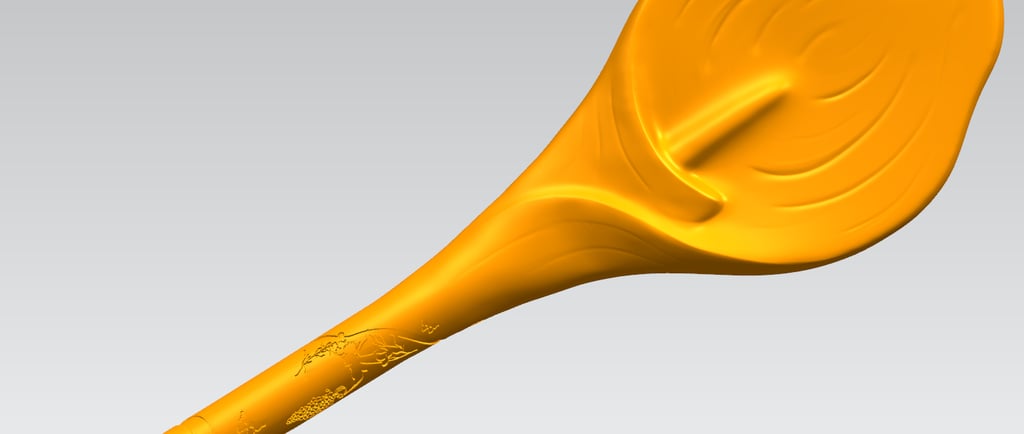

A netizen sent me this question today. It wasn't until I saw the images he shared that I understood what he meant. Here’s the situation: after casting, the product had internal shrinkage porosity, which was not visible from the outside. However, during machining, the shrinkage cavities were exposed, leading to the term “304 machining-induced shrinkage porosity.” Thus, the root cause is casting shrinkage located at the root of the ingate. The problem we need to solve is precisely this shrinkage at the ingate root. Some might say, if there’s shrinkage at the ingate, why not simply increase its size? What’s so difficult about that? In reality, it’s not that straightforward. For thick-walled castings, enlarging the ingate may be beneficial, but for thin-walled castings, it can be disastrous. Increasing the ingate size in thin sections artificially creates a thermal contact hotspot, which actually increases the likelihood of shrinkage porosity.

In fact, this friend’s casting has uneven wall thickness—one of the most troublesome types. A high pouring temperature risks shrinkage, while a low pouring temperature may cause incomplete filling. I’ve encountered this exact casting before, and it is quite challenging. Today, let’s discuss how to identify the underlying patterns amid such confusing symptoms. According to this friend, his product has a 25% rejection rate. The pouring parameters are: pouring temperature 1680–1700°C, mold preheat temperature 1100–1150°C, using a 150 kg medium-frequency furnace for full-furnace pouring. The shrinkage defects appear randomly, and he hopes I can help clarify the situation.

Of course, I’ve seen this product before and am aware of some of its issues. However, the problem we faced back then was different—we had shrinkage on the inner side of a large circular flange due to a small inner radius. At that time, we used a gate-shaped cluster, eight pieces per set, with a high rejection rate. Lower temperatures made shrinkage even worse. On a sudden inspiration, we tried adding insulating material, and unexpectedly, the qualification rate improved significantly. But this part requires high-temperature pouring, so we adopted a half-furnace pouring method. I often mention furnace matching—combining high-temperature and low-temperature products in one furnace pour—and this part was typically poured in the first half.

Based on this experience and considering the pouring temperature of 1680–1700°C provided by the friend, it’s clear that this part requires high-temperature pouring and may not tolerate low temperatures well. Therefore, I asked whether he used insulating material during pouring and whether he poured a full furnace or half. It turns out he used insulating material and poured the full furnace.

From my earlier experience and analysis, since this part favors high temperatures, the next question arises: if it prefers high temperatures, can full-furnace pouring maintain that temperature, both for the metal and the mold? That’s the first issue. The second is whether the 25% rejection occurs in the first 25% or the last 25% of the pour—this is something we must clarify. Following the earlier reasoning, defects likely appear in the last 25%, but this still requires verification. According to the friend, the shrinkage defects seem random. Actually, this isn’t accurate. From the images he shared, shrinkage consistently occurs at the ingate of the smaller end—that’s the pattern. If there’s a 25% defect rate, it indicates that this ingate is unsuitable for certain pouring conditions, such as low temperature; we just haven’t identified the pattern yet.

The casting cluster is arranged horizontally with six pieces across two branches, meaning some are closer to the pouring cup and others farther, affecting feeding differently. Thus, the third step in identifying the pattern is to determine which positions in the cluster have more shrinkage defects, which will help us pinpoint the root cause.

Some may ask: if shrinkage isn’t visible initially and only appears during machining, what should we do? In such cases, to trace the culprit, we must use the most straightforward method—marking. Mark all products from one furnace pour and trace back defect locations based on machining results.

Here, I’ve provided an example and a way of thinking: how to identify the root cause of casting defects amid confusing symptoms. Generally, we start by looking for defect patterns across the entire furnace batch. For instance, divide the furnace pour into early, middle, and late sections to see which has more issues. If no pattern emerges there, we examine the cluster—where defects are most frequent, such as incomplete filling being more common at the top of the cluster. Sometimes, to test the tolerance of pouring temperature, we take the first, middle, and last clusters and look for patterns among them.

For this casting, with such a high defect rate, there must be a reason for the shrinkage. As long as we carefully investigate, a pattern will certainly emerge. In fact, for this casting, I believe several aspects are worth discussing: the ingate size at the smaller end, the gating system design, and the feasibility of full-furnace pouring. For example, we could try half-furnace pouring to see if the qualification rate improves, or slightly reduce the ingate size at the smaller end, or modify the gating design. These are all potential directions for improvement.